Have you ever heard of food or fibre forensics? It’s a bit like interviewing the lead detective on a crime scene to learn the truth about where our produce really comes from.

Fraud is alive and well in the global supply chain. So how do you know whether that Egyptian Cotton really comes from Egypt or that grass-fed Australian beef is as advertised?

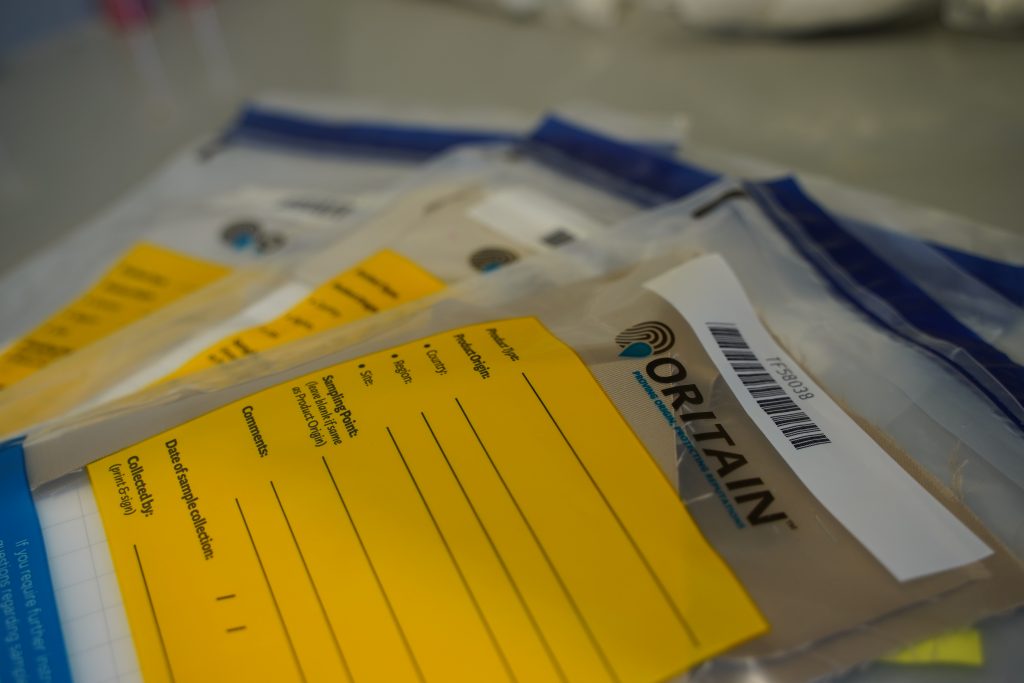

New Zealand company Oritain are the scientists untangling that web – tracing the provenance of an item, not just to country of origin but in some cases back to a specific region. To learn more about the process, the company’s Head of Strategic Sales Sam Lind takes us through the details.

Representatives from the organisation travel the world, pulling samples from the land to build a data library. Part of the success of tracing an item depends on having a background sample – something that comes from that region to compare with items of uncertain origin.

“We do soil. We also do direct sampling from the product commodity that we are investigating. So, cotton from South America or Australia. Or citrus. Or it might be coffee and cocoa from West Africa,” explains Sam.

All these attributes we call a chemical fingerprint. That chemical fingerprint is taken up by plants and animals local to that environment. That then provides a connection between that product and its source.”

Investigators use this information to confirm a company is selling 100% honey that hasn’t been watered down or is trading in a genuine product.

“Nature provides us everything that we need. The geo-chemistry of your environment differs depending on where in the world you are. People deep into soil science obviously know that.

“The climate differs between dry, wet, warm, cold. All these attributes we call a chemical fingerprint. That chemical fingerprint is taken up by plants and animals local to that environment. That then provides a connection between that product and its source,” Sam says.

Global libraries

Oritain has large global libraries used to establish a background reference point for origin. Some analytical chemistry extracts that so-called fingerprint from the sample library and then statistics will confirm where an item of concern has actually originated.

Nature provides us everything that we need. The geo-chemistry of your environment differs depending on where in the world you are.”

“Essentially, we look at the attributes that are common for this origin, and the attributes that differentiate this from that. We then have the capability to take an unknown or a claimed source product and do the analysis and compare it back to the reference.”

It’s a little like an autopsy for materials and interestingly, the background science is in fact a forensic method.

Through our global reference library we can then establish what is unique to an area.”

“Originally, when there was a Jane Doe or a John Doe for particular case, they’d try to track where this person has been. There are a number of cases when that was important and our founders looked at it and said instead of applying this to a forensic problem, can we apply it to a supply chain commercial problem,” says Sam.

Fighting food fraud

The science can determine which country, region and in some cases which farm the product has come from.

There are certain products that absorb a lot more environmental chemical attributes than others. Tea, rice and cotton contain a lot of information. To get to the bottom of a supply chain query, Oritain has been known to send in mystery shoppers to export markets to purchase product on behalf of their client.

“We bring that back, test it and check if there are areas of risk in the supply chain,” Sam says.

Food fraud is hard to quantify globally because of a lack of data. “We use mystery shoppers to identify our own results. Our own objective data. Then, we have some real information we can take back to industry,” Sam explains.

The word fraud connotes a level of complicity but quite often a retailer could unwittingly sell a product that been sold to them dishonestly. Big retailers like Country Road are key clients of Oritain to ensure that doesn’t happen to them.

“There is intentional non-compliance and there is non-compliance just because of the nature of the supply chains,” says Sam.

Preserving reputations

The fastest area of growth for Oritain are those large textile retailers who want to preserve their reputations and save themselves from any controversies arising from a bad supply chain.

Also, large food exporters like A2 Milk and various meat and fruit producers have become clients. It’s about delivering what’s being promised to consumers and to shareholders. Specificially, to get to the bottom of all that, scientists look at a product’s mineral profile (elements on the periodic table) and its stable isotopes (directly related to the climatic conditions).

“These two chemical attributes largely make up the fingerprint that we are looking for,” explains Sam.

As an example, to verify a piece of cotton is Australian, Sam takes us through the process.

The science behind food and fibre fingerprints

“A lot of Australia uses irrigation and the majority of it is irrigation with large storage ponds. We might be having two good years in five, but we’ve got storage ponds. You’re going to get evaporation over that time.

“It’s going to change the water profile compared to some places around the world where it’s all rainfall; some places around the world where it’s all bore water; or if you are in the San Joaquin Valley of California, you’ve got snow melt – that’s where your irrigation water comes from.

“So, all these different climatic indications give a unique profile and through our global reference library we can then establish what is unique to an area,” explains Sam.

Sam says he’s most proud of how they have taken something that’s very lab based and scaled it to be relevant to global commerce. So, next time you are watching your favourite crime drama on television, spare a thought for the same techniques that are being applied to the food and fibre you’re buying in the shops.

Hear more stories just like Sam’s by subscribing to the Telling Our Story podcast on iTunes and follow podcast host Angie Asimus on Instagram for more updates.

Irrigation farming tends to be more expensive.